Written by Dr Jean-Pierre Eyanga Ekumeloko,

an Irish citizen and businessman living in Dublin,

and originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

www.gee-consulting.com

Feb 2012

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is probably the African country with the strongest historical links with Ireland. There are mainly two I would like to talk about.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is probably the African country with the strongest historical links with Ireland. There are mainly two I would like to talk about.

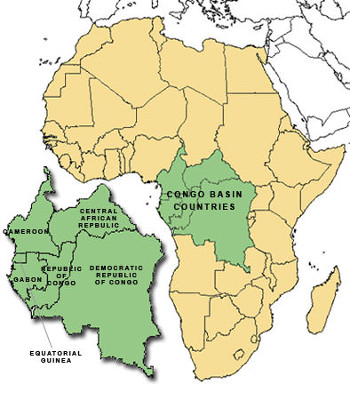

The first has to do with Roger Casement who worked there. I remember hearing his name for the first time in 1973, when I was in 5th Year in a secondary school, Boboto College, in Kinshasa, capital city of this large country of 2,345,000 sq k in Central Africa.

I know that Congolese people are very grateful to Roger Casement. To understand this we need to revisit the history of Congo. In 1876, because of his desire for glory, King Leopold II of Belgium founded the International African Society, a “civilizing” enterprise for Africa. After also creating the International Congo Society in 1878, with a more imperialist vision, he sent Henry Morton Stanley to Congo for the second time from 1879 to 1885 to prepare for the formation of the Congo Free State. Unfortunately, the French Government objected to his plans.

Thus, in 1884-85, the Berlin Conference was called for by Portugal but organised by Bismarck, the first German Chancellor, to gather the representatives of the most powerful western countries, including Austria–Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, the UK, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden-Norway (union until 1905), the Ottoman Empire, and the US. The meeting’s aim was clear: to plan the scramble for Africa, regulate colonisation and devise rules for trade in the continent.

A key outcome of the meeting was that the Free State of the Congo was made essentially the property of Leopold II. He exploited its natural resources – especially rubber and ivory – exactly like a greedy and unscrupulous businessman. Although their resistance was fierce, the Congolese people were submitted by Leopold’s collaborators to massive, harsh and cruel human rights abuses.

In 1900, a denunciation campaign run by ED Morel and many other Reformists took place in Europe and in America. When King Leopold II’s cousin Queen Victoria died, a decision had to be made about how to continue treating the Congo. In 1903, the House of Commons commissioned Roger Casement, an Irishman working as British Consul at Boma, to investigate the accusations of human rights abuses in the Congo Free State. His long and well-detailed report was a real testimony which exposed all the abuses carried out by the King’s people. The Casement report was delivered in 1904.

In fact, it contained 40 pages of parliamentary papers and 20 other pages of individual statements that Mr Casement compiled. There were many accounts of razzias, killings, mutilation, kidnapping and cruel beatings of the native population by soldiers of the Congo administration of King Leopold. The British government sent copies to the Belgian government and all the signatories to the Berlin Agreement in 1885. The Casement report was confirmed in every detail by another report written through an independent inquiry set up by the Belgian government.

According to William Roger Louis, a distinguished historian at the University of Texas at Austin: “Casement gathered evidence that enabled the British government to attack the Congo State on grounds of maladministration.[…] Convinced that only a humanitarian crusade could abolish the evils of the Leopoldian regime, Casement inspired ED Morel to found the Congo Reform Association. Through his dual capacity of civil servant and humanitarian, he attempted, in his own words, to choke off King Leopold ‘as a “helldog” is choked off’.”

In Congo, historians and other intellectuals are convinced that Casement’s report was key to persuading Leopold to finally relinquish his personal holdings in Africa and Belgium’s annexation of the Congo as a colony in 1908. Even though it was a transfer of the territory from one entity to another, moving from a totally business-led bloody exploitation to an exploitation colonisation, this development released the Congolese from a completely evil system. And they will never forget it.

Hannah Arendt, a German American political theorist, thinks there was an estimated minimum population loss of 11.5 million. Isidore Ndaywel è Nziem, a Congolese scholar, puts the figure at roughly 13 million. Some historians consider that, without doubt, what happened in the Congo was one of the great catastrophes of modern times.

This happened almost 100 years ago. It is bizarre that today, 50 years after securing independence, Congo still faces almost the same ghosts. For the British and Irish governments and human rights activists, the challenge is their duty to keep the noble actions of their ancestors in DRC alive and unspoiled. Didn’t Court Gully and James Lowther, speakers in the UK House of Commons between 1895 and 1921, work to see Congolese people live peacefully? Did the House of Commons, British Government, ED Morel and Roger Casement really care about the Congolese people or not? If they did, nobody should spit on their memory, especially now that DRC is being betrayed and used as prey.

References:

- http://hcmilkowski.wordpress.com/2010/02/10/why-should-you-know-about-the-casement-report/

- http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract;jsessionid=F5DFC388C5BF7A214A4FCD8F6C1266F2.journals?fromPage=online&aid=27797

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_Casement

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E._D._Morel

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlin_Conference_%281884%29

- http://www.enotes.com/king-leopold-ii-congo-reference/king-leopold-ii-congo

Copyright © 2011, DPNLIVE – All Rights Reserved

{jcomments on}