The virus gains attention as it spreads through hockey.

While the National Hockey League makes less headlines than some other major sports leagues in the USA, its outdoor stadium series, highlighted by the Winter Classic on New Year’s Day gets its share of attention. Recently, the league has made headlines for a less desirable reason. More than 20 players on five teams and several referees have been diagnosed with the mumps virus.

While the National Hockey League makes less headlines than some other major sports leagues in the USA, its outdoor stadium series, highlighted by the Winter Classic on New Year’s Day gets its share of attention. Recently, the league has made headlines for a less desirable reason. More than 20 players on five teams and several referees have been diagnosed with the mumps virus.

The NHL is the perfect environment for it to spread, players share water bottles and being in close proximity, it is easy to get sneezed, coughed and spit on. Even one of the NHL’s biggest stars, Sidney Crosby of the Pittsburg Penguins contracted the disease. It takes 12 days or more for symptoms to occur, so a player may be harboring the virus and seem perfectly healthy during this period. It is not clear who the first player was that contracted the mumps virus but the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) believes it began in October and signs point to the Anaheim Ducks or Minnesota Wild as possible culprits. It is possible that other teams may have been infected with the virus as well.

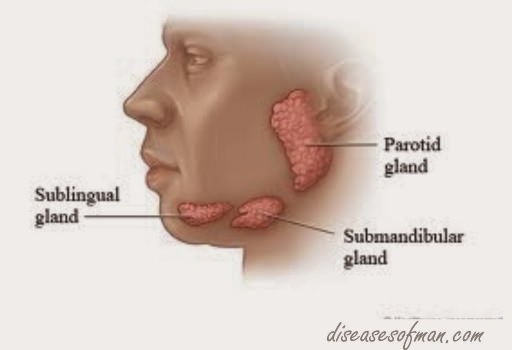

Mumps, also called epidemic parotitis, is a viral disease caused by the mumps virus. It affects the parotid glands, one of the three types of salivary glands and is situated in front of the ear. Symptoms can appear 2 to 3 weeks after being infected and include fever, headache, and weakness, but the signature symptom of mumps is swelling and pain in the parotid gland. It is spread through saliva and can be transferred through sneezing, coughing, or by sharing utensils. There is no treatment for the disease but most people do not have any complications once the virus has passed. Mumps was once a common childhood disease but has been greatly reduced thanks to the MMR (Measles, Mumps, and Rubella) vaccine.

Sidney Crosbey of the Pittsburg Penguins with swelling on the side of his faceMumps Vaccinations began in 1949 in the U.S. and the first vaccine was not very effective at preventing the virus. In 1967 a new version of the vaccine was developed and in 1971, it was combined with the vaccines for measles and rubella. In 1989, a second dose of the vaccine was introduced, changing the protocol to two treatments of MMR. Prior to 1967, about 186,000 cases of mumps were reported each year according to the Centers for Disease Control. Since then, that number has dwindled to an average of 265 cases per year, although outbreaks have occurred, the largest in recent times being 2006 with 6,339 cases reported, most of which were on college campuses.

Sidney Crosbey of the Pittsburg Penguins with swelling on the side of his faceMumps Vaccinations began in 1949 in the U.S. and the first vaccine was not very effective at preventing the virus. In 1967 a new version of the vaccine was developed and in 1971, it was combined with the vaccines for measles and rubella. In 1989, a second dose of the vaccine was introduced, changing the protocol to two treatments of MMR. Prior to 1967, about 186,000 cases of mumps were reported each year according to the Centers for Disease Control. Since then, that number has dwindled to an average of 265 cases per year, although outbreaks have occurred, the largest in recent times being 2006 with 6,339 cases reported, most of which were on college campuses.

Statistics show that most of the reported cases of mumps occur in individuals that have received the MMR vaccine (95% of the cases in the 2006 outbreak were vaccinated). If the vaccine is supposed to prevent the disease, why are people getting it? The vaccine is about 80% effective against the mumps virus and decreases over time. Receiving a second dose of the vaccine raises the effectiveness level to almost 90%. Over time, MMR’s effectiveness against the mumps decreases slightly, making people more vulnerable to the disease. The reason behind this is the human immune system. Again, over time, immune memory of antibodies decreases. By comparison, B cells and T cells (antibodies) are much better at recognizing the measles and rubella viruses.

The three major salivary glands Mumps affects the parotid glandShould Americans be worried about the mumps virus? An outbreak of mumps cases among vaccinated individuals does not mean people should choose not to receive the vaccine. Vaccination has been the best method of reducing spread of the virus with reported cases reduced by 99%. Even though it has been making headlines, the virus has never really completely eradicated in the United States. Despite a high success rate, individuals who receive both doses of the vaccine still have a chance of contracting the virus. Half of the world’s population does not even receive a mumps vaccination of any kind and hundreds of thousands of cases occur each year. This makes travelers an easy vessel for bringing the virus stateside.

The three major salivary glands Mumps affects the parotid glandShould Americans be worried about the mumps virus? An outbreak of mumps cases among vaccinated individuals does not mean people should choose not to receive the vaccine. Vaccination has been the best method of reducing spread of the virus with reported cases reduced by 99%. Even though it has been making headlines, the virus has never really completely eradicated in the United States. Despite a high success rate, individuals who receive both doses of the vaccine still have a chance of contracting the virus. Half of the world’s population does not even receive a mumps vaccination of any kind and hundreds of thousands of cases occur each year. This makes travelers an easy vessel for bringing the virus stateside.

The spread of the Mumps virus is probably not going away anytime soon. According to Dr. Greg Wallace, the Lead of the domestic measles, mumps, rubella, and polio team at the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia says that the NHL would need to go about 50 days without a new case before being considered free of the disease. With new players being diagnosed each week, there is still a long way to go before this problem has been contained.

By Daniel J. Steiger

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

To see further articles on the environment by Daniel please go to http://www.dpnlive.com/index.php/news/general-news/environment

You can Tweet, Like us on Facebook, Share, Google+, Pinit, print and email from the top of this article.

Copyright © 2015, DPNLIVE – All Rights Reserved.